Our adventure to Haleakala began at the end of the Summer of 2011. My wife Danielle's family was planning a celebration of her parent's 50th wedding anniversary in Hawaii. Her older brother Ross Cunniff, also an amateur astronomer, suggested that if we were going to be in Hawaii during the Summer of 2012, why not time the trip to coincide with the transit. That plan was heartily endorsed by the astronomy buffs in the family.

From an astronomical observation point of view, weather patterns suggested we would need to find a high elevation site to ensure clear skies. This left us with two basic choices: Haleakala on Maui and Mauna Kea on Hawaii ... not surprisingly, the two sites with professional observatories. Mauna Kea is higher, at 14,000 feet, but we had visited it two years ago and knew that it would be physically difficult to manage10 hours of activity at the summit. The Mauna Kea Visitor Center at 9,300 ft. elevation is much better, but we did not recall it having a very good western horizon. In the end, we chose Haleakala because we thought it would be less crowded and would be high enough at 10,000 feet to be above the clouds but not as likely to give us altitude sickness. Danielle also liked the symbolism of watching the transit from the "House of the Sun."

After consulting aerial views, I proposed that we arrive on the mountain mid-morning (after the sunrise crowd left) and that we attempt to set up at Pu'u Ula'ula or the "Red Hill Summit" observation area located at 10,023 ft. We later had a possible lead on getting permission to setup within the Maui Space Surveillance Complex, but that fell through due to security and logistics concerns when the observatory outreach staff began to plan for the anticipated crowds.

Once we decided on the site, Danielle and I needed to figure out what sort of equipment to bring along. So began several months of indecision. We wanted to be able to take good pictures of the transit, but we were limited by what we could take as checked and carry-on luggage. For a mount, I purchased a used Losmandy GM-8 from a local astronomer. This offered a stable platform that I could also use for deep sky imaging on the trip and in future travels. I was able to get the complete mount and accessories into two hard cases, each just at 50 pounds. For a scope, we debated between several choices: a simple white-light filter for a telescope or camera, a Herschel wedge, a budget H-alpha telescope such as the PST, and a nicer H-alpha telescope such as a Lunt. In the end, we chose to bring a Lunt LS60T/PT and a simple Kendrick film cover for our DSLR and 400mm lens with a 2x teleconverter, all of which traveled in carry-on Pelican cases. Ironically, Ross ended up bringing the other combination, a Baader Herschel wedge and a PST. I purchased the Lunt last fall and had several months to practice imaging with it. I also figured out what combinations of optics would result in what image scales. However, despite my best effort to anticipate from what side of the field of view Venus would first appear, I still got it backwards.

We also took advantage of the partial annular solar eclipse on May 20 here in Austin to do a dry run with the Lunt and the DSLR setup. For the eclipse, we imaged for 2 hours in 90 degree weather at an elevation about 300 feet above sea level. We knew that 7 or more hours at 50 degree Fahrenheit at 10,000 feet would be much more challenging.

On June 5, the day of the transit, Danielle, Ross, and I got up at dawn and headed out for the 2 hour drive to the summit. It took two cars to bring all of the equipment. The road to Haleakala is popular with cyclists, mostly descending the 30 miles of switchbacks after sunrise. Unbelievably, while we were chatting on the summit, we met a guy who had cycled UP the entire road ... and it was not Lance, though he was wearing a "Mellow Johnny's" shirt!

At sea-level the sky was overcast and the temperature was in the mid-70s. We punched through all of the clouds long before we got to the summit. Finally arriving at the summit we had left even the scrub behind and were in a terrain that looked like Mars, with highs in the low 50s. This view shows that last leg of the climb. Red Hill Summit is in the center with the observation shelter just to the left. To the far right in the distance is the observatory complex.

Once on the summit we had an unobstructed view in all directions. To the East was the main crater of Haleakala below us, the clouds slowly creeping up over the crater rim.

Our main weather concern had been the winds which had plagued Maui for the previous week. Sure enough, when we got to the summit at 9 am, the winds were strong, with gusts that made walking difficult. This did not bode well for observing. After some discussion about going back down to a lower elevation, we chose to set up right in the lee of the observation shelter. Even though the winds died down by transit time, this proved to be a fortuitous choice. Not only did this give us a sheltered spot with a wall and drop-off to the West, we also ended up right next to where other public-outreach activities were planned, unbeknownst to us.

Others astronomers showed up later, including some French observers hoping for the same spot an hour later. I think they may have gone down to the visitor's center area; we did not have a chance to see them again. We set up as quickly as possible and even so weren't quite ready when the transit started; among other things, I forgot to change the elevation of the mount from the 32 degrees latitude of Austin to the correct 20 degrees for Hawaii, which we corrected in mid-transit. In the picture below, Ross's setup is on the left and I am on the right. Danielle took charge of the white-light camera and also took pictures of the day's activities with her point and shoot.

Right next to us, Gilson Killhour (shown in the red jacket below), a math teacher from the Seabury Hall school on Maui, set up a "Citizen Scientist" booth which included a cool "Sun Spotter" device which projected a large image of the transit and major sunspots. He was joined by other volunteers and by a park ranger, Keith, who was very helpful throughout the day.

Between us all, we kept up a flow of explanations and demonstrations with the non-stop stream of visitors to the site over the course of the day. When we planned this expedition, I had not anticipated how good of a public outreach opportunity this would be. I am guessing that there are now many dozen photos of my laptop screen out there. Kids particularly seemed to enjoy seeing the detail on the surface of the sun, while adults were awed by the power and size of solar prominences.

Our equipment worked very well though I had some problems with my pressure-tuned Lunt telescope losing pressure very quickly. I am still not sure what was going on since it functions fine at sea-level; perhaps it wasn't built for the thinner air at 10,000 ft. To compensate for this, I needed to completely unscrew the pressure knob and re-tune before each of my 5 minute spaced shots. Thus, reaching up to adjust the tuner became the position to assume throughout the day

By the end of the day, we were all totally exhausted. We brought water and some food, but I am sure we did not drink nearly enough and the sun was pretty intense at that elevation. The restrooms were more than a mile away at the Visitor's Center, which meant that we had to take turns so that someone was always watching each set of scopes and capturing images.

As the crowds assembled to watch the setting sun, we began to take down our equipment. Watching the sunset from Haleakala is breath-taking with the deep blue sky and the cloud layer well below you.

One issue we hadn't resolved before heading to Maui was what we would do with the marine batteries we would be purchasing, since we couldn't take them home with us. Our conversation with Gilson revealed that he taught engineering-prep classes which included lots of experimental work. He was quite happy to accept our donation of the batteries to his school. Just before going to the airport on our last day, we dropped off the batteries at Seabury Hall.

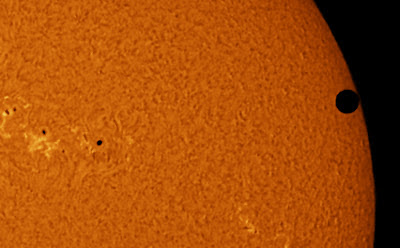

Once back home, we began the post processing of our image data. In all, we were pleased with the results. The Lunt LS60T/PT suffered a slight loss in detail due to the altitude but, other than the continuous re-tuning hassle, generated excellent results. The full frame image below is a 2x1 mosaic with separate exposures for surface detail and prominences. This was taken at "second contact" near the beginning of the transit. The constituent images were generated from 30sec AVI clips taken with a DMK41.AU02 video camera. You can see some interesting activity all over the solar disk. Too bad there were not some spectacular prominences active at the time of the transit.

I also assembled the entire sequence of images over the course of the transit into an animation posted on YouTube. Watch for the nice flare erupting in the large bright region.

The enlarged shot below is "third contact" at the end of the transit. For me, this is a pretty special shot since this is the one that would have been impossible to get from the mainland.

Using the DSLR and an 400mm Canon lens with 2x extender (equivalent to a 1280mm focal length at f/11), we got some very nice white-light shots. Though this configuration does not show granulation, filaments, or prominences, the sunspot details are much better. The tear-drop effect is also more noticeable in this "second contact" image. Note that this image is rotated differently than the solar telescope and shows Venus entering at the upper right, as it appeared to the naked eye through solar glasses. Many visitors on Haleakala also reported being able to see Venus naked eye mid-way through the transit.

In all, a memorable trip to experience the 2012 Venus Transit and the special place which is Haleakala, Maui. To get Ross's perspective on the transit, you can read his blog post.